Photographs by Kenji Aoki for TIME

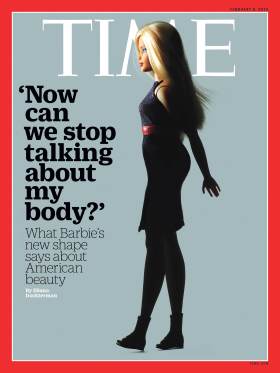

Inside the biggest change in barbie’s 57-year history–and what it says about American beauty ideals

Part 1

Barbie’s dress won’t fit.

I’m sitting in a bright pink room at Mattel’s headquarters in El Segundo, Calif., playing with a Barbie that only 20 people in the world know exists. Her creation has been kept so secret that the designers code-named the endeavor Project Dawn so that even their spouses wouldn’t be tipped off to her existence.

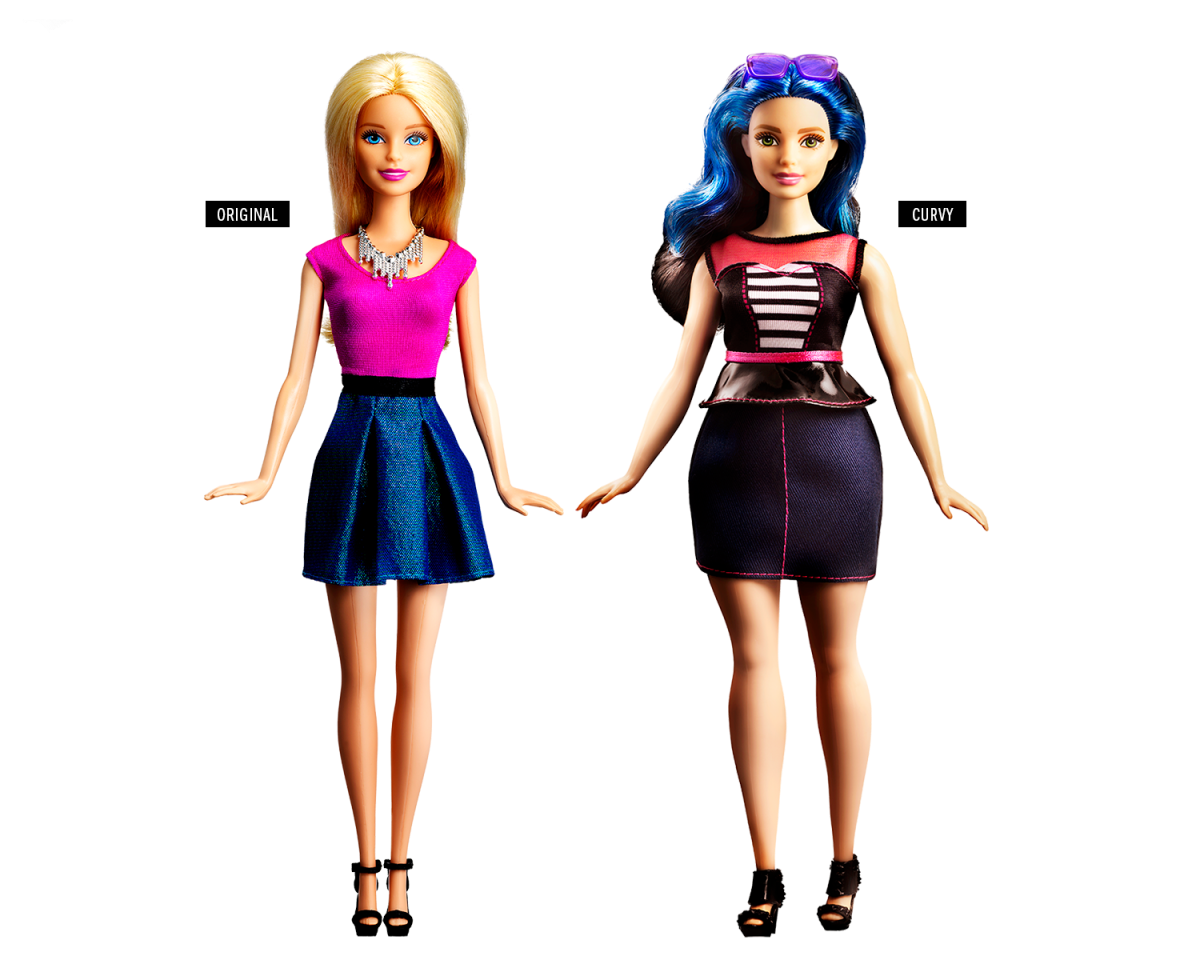

Like every girl who has ever played with the most popular toy in history, I yank her clothes off and try to put on a new dress. It’s a blue summery frock, cinched tightly at the waist with a black ribbon. I try to tug it over her head, but the waistline gets stuck at her shoulders, her blond mane peeking out from the neckline. “Try going feet first,” the lead designer suggests, and I do. No good. Her plump bottom gets stuck in the same spot. Yes, plump. Barbie’s got a new body. Three new bodies, actually: petite, tall and curvy, in Mattel’s exhaustively debated lexicon, and beginning Jan. 28 they will be sold alongside the original busty, thin-waisted form on Barbie.com. They’ll all be called Barbie, but it’s the curvy one—with meat on her thighs and a protruding tummy and behind—that marks the most startling change to the most infamous body in the world.

It’s a massive risk for Mattel. Barbie is more than just a doll. The brand does $1 billion in sales across more than 150 countries annually, and 92% of American girls ages 3 to 12 have owned a Barbie, thanks in part to her affordable $10 price tag. She’s been the global symbol of a certain kind of American beauty for generations, with brand recognition that’s up there with Mickey Mouse. M.G. Lord, a Barbie biographer, once said she was designed “to teach women what—for better or worse—is expected of them in society.”

The company hopes that the new dolls, with their diverse body types, along with the new skin tones and hair textures introduced last year, will more closely reflect their young owners’ world. But the initiative could also backfire—if it’s not too late altogether. Adding three new body types now is sure to irritate someone: just picking out the terms petite, tall and curvy, and translating them into dozens of languages without causing offense, took months. And like me, girls will strip curvy Barbie and try to put original Barbie’s clothes on her or swap the skirts of petite and tall. Not everything will Velcro shut. Fits will be thrown, exasperated moms will call Mattel. The company is setting up a separate help line just to deal with Project Dawn complaints.

But staying the course was not an option. Barbie sales plummeted 20% from 2012 to 2014 and continued to fall last year. A line of toys designed to teach girls to build, Lego Friends, helped boost Lego above Mattel as the biggest toy company in the world in 2014. Then Hasbro won the Disney Princess business away from Mattel, just as Elsa from the film Frozen dethroned Barbie as the most popular girl’s toy. The estimated revenue loss to Mattel from Elsa and the other Disney Princesses is $500 million.

Meanwhile, American beauty ideals have evolved: the curvaceous bodies of Kim Kardashian West, Beyoncé and Christina Hendricks have become iconic, while millennial feminist leaders like Lena Dunham are deliberately baring their un-Barbie-like figures onscreen, fueling a movement that promotes body acceptance. In this environment, a new generation of mothers favor what they perceive as more empowering toys for their daughters. Elsa might be just as blond and waif-thin as Barbie, but she comes with a backstory of strength and sisterhood. “The millennial mom is a small part of our consumer base,” concedes Evelyn Mazzocco, head of the Barbie brand, “but we recognize she’s the future.”

Part 2

The board behind Mazzocco’s desk is filled with words like out of touch, materialistic, not diverse.

She tacked them up shortly after she took over Barbie in 2014, part of a massive shake-up at Mattel during which president and COO Richard Dickson put people with creative backgrounds at the head of several brands, hoping they would come up with more-innovative solutions to Mattel’s sinking sales. The first thing Mazzocco did in that role was survey Barbie’s haters.

“I wanted to remind myself every time I came to work about the reality of what is going on with the brand,” says Mazzocco, who has three daughters whom she uses as her “own little focus group.” Not that she needed the reminder: she routinely receives hate mail and even death threats over Barbie’s body.

Barbie has courted controversy since her birth. Her creator, Ruth Handler, based Barbie’s body on a German doll called Lilli, a prostitute gag gift handed out at bachelor parties. Her proportions were designed accordingly. When Handler introduced Barbie (named after her daughter Barbara) in 1959 at the New York Toy Fair, her male competitors laughed her out of the room: nobody, they insisted, would want to play with a doll with breasts.

Still, Barbie’s sales took off, but by 1963 women were protesting the same body men had ridiculed. That year, a teen Barbie was sold with a diet book that recommended simply, “Don’t eat.” When a Barbie with pre-programmed phrases uttered, “Math class is tough,” a group called the Barbie Liberation Organization said the doll taught girls that it was more important to be pretty than smart. They switched out Barbie’s voice box with that of GI Joe so that the blonde cried, “Vengeance is mine,” while the macho warrior enthused, “Let’s plan our dream wedding.”

Mattel argues that the criticism was misplaced—that Barbie was a businesswoman in 1963, an astronaut in 1965 and a surgeon in 1973 when 9% of all doctors were women. “Our brand represents female empowerment,” argues Dickson. “It’s about choices. Barbie had careers at a time when women were restricted to being just housewives. Ironically, our critics are the very people who should embrace us.”

Mattel has also long claimed that Barbie has no influence on girls’ body image, pointing to whisper-thin models and even moms as the source of the dissatisfaction that too many young girls feel about their bodies. A handful of studies, however, suggest that Barbie does have at least some influence on what girls see as the ideal body. The most compelling, a 2006 study published in the journal Developmental Psychology, found that girls exposed to Barbie at a young age expressed greater concern with being thin, compared with those exposed to other dolls.

But it was only when moms started voting with their dollars that Mattel had to reassess these criticisms. In the mid-2000s Barbie faced her first serious competition after years of maintaining about 90% market share of the doll sector. Bratz, the edgy, bug-eyed dolls with their own smartphones and lip gloss, were “eating Barbie’s lunch in the older-girl demographic, and Disney Princess was chomping away at the younger-girl demographic,” explains Dickson. “Barbie was having an identity crisis.”

At first, this wasn’t a major problem for Mattel. Dickson was brought in in 2000 to expand the Barbie brand from dolls to apparel, TV shows and gaming. That’s when Barbie got her own interactive website. (She also has her own show that streams on Netflix.) The Barbie brand’s sales went up even as the doll’s sales sank. And Mattel as a whole prospered. The company was producing the Disney Princess dolls through a licensing deal, and to combat the Bratz problem, it created its own line of cutting-edge dolls, Monster High.

But in 2012, Barbie global sales dropped 3%. They dropped another 6% in 2013 and 16% in 2014. And the dominance of Frozen’s Elsa signals more trouble ahead. Even two years after the film’s release, the allure of Frozen hasn’t abated. At a Los Angeles Target, I locate Barbie in the toy aisle, beaming down at me from her dream house (pink convertible sold separately). On the next shelf over sits Elsa in a box that invites you to press a button to hear her sing. I press. As the doll begins to belt out the girl-power anthem “Let It Go,” children—girls and boys—come running from all directions screaming, dancing, one explaining to her mom why they need yet another variation of the Elsa doll in their house. I make a hasty retreat as the mother begins to look around for the idiot who started playing “Let It Go” in the toy aisle during the holiday season.

Therein lies Barbie’s problem. As much as Mattel has tried to market her as a feminist, Barbie’s famous figure has always overshadowed her business outfits. At her core, she’s just a body, not a character, a canvas upon which society can project its anxieties about body image. “Barbie has all this baggage,” says Jess Weiner, a branding expert and consultant who has worked with Dove, Disney and Mattel to create empowering messaging for girls. “Her status as an empowered woman has been lost.”

Part 3

With all that in mind, Kim Culmone, head of design, posed a challenge to her team:

If you could design Barbie today, how would you make her a reflection of the times? Out of that came changing Barbie’s face to have less makeup and look younger, giving her articulated ankles so she could wear flats as well as heels, giving her new skin tones to add diversity and then of course changing the body. While curvy Barbie’s hips, thighs and calves are visibly larger than before, from the waist up she is less Jessica Rabbit than she is pear-shaped. Mattel refuses to discuss the actual proportions of the new dolls or how it came to decide on them.

What’s clear in listening to the team discuss the project is that every step was taken on tiptoe. “It’s a personal issue because almost every woman has owned a Barbie, and every woman has some relationship with or opinion about Barbie,” says Culmone. During one meeting, designers, marketers and researchers fixated on the shoe problem. There will now be two Barbie shoe sizes, one for curvy and tall and another for original and petite. “We can’t label them 1, 2, because someone will read into that as saying one’s better than the other,” Barbie designer and former Project Runway contestant Robert Best explains. “Plus, we have to put the Barbie branding on every single object, and the shoes are so tiny.” They finally land on a B for one shoe size and Barbie’s face on the other. Moms will have to puzzle out which is which when they find a miniature stiletto jammed between their couch cushions.

Indeed, the additional bodies are a logistical nightmare. Mattel will sell the dolls exclusively on Barbie.com at first while it negotiates with retailers for extra shelf space to make room for the new bodies and their clothes alongside the original. There are a seemingly infinite number of combinations of hair texture, hair cut and color, body type and skin tone. And then there’s the issue of how to package the dolls. Mothers surveyed in Mattel focus groups expressed concern over giving the new dolls to their daughter or a friend of their daughter’s. What if a sensitive mom reads into the gift of a curvy doll a comment on her daughter’s weight? Mattel decided to sell the dolls in sets to avoid this problem, but then it had to figure out which dolls to sell together to optimize diversity and marketability.

“Yes, some people will say we are late to the game,” says Mazzocco. “But changes at a huge corporation take time.”

Part 4

“Hello, I’m a fat person, fat, fat, fat,”

A 6-year-old girl giving voice for the first time to curvy Barbie sings in a testing room at Mattel’s headquarters. Her playmates erupt in laughter.

When an adult comes into the room and asks her if she sees a difference between the dolls’ bodies, she modifies her language. “This one’s a little chubbier,” she says. Girls in other sessions are similarly careful about labels. “She’s, well, you know,” says an 8-year-old as she uses her hands to gesture a curvier woman. A shy 7-year-old refuses to say the word fat to describe the doll, instead spelling it out, “F, a, t.”

“I don’t want to hurt her feelings,” she says a little desperately.

As always, Barbie acts as a Rorschach test for the girls who play with her—and the adults who evaluate her. It’s a testament to anti-bullying curriculums in elementary schools that none of the girls would use words like fat in front of an adult, which Barbie’s research team says wasn’t true even three years ago. Still, the girls learning the ways of political correctness do not as wholeheartedly embrace the new dolls as their moms.

“We see it a lot. The adult leaves the room and they undress the curvy Barbie and snicker a little bit,” says Tania Missad, who runs the research team for Mattel’s girls portfolio. “For me, it’s these moments where it just really sets in how important it is we do this. Over time I would love it if a girl wouldn’t snicker and just think of it as another beautiful doll.”

It’s a sign that even kids as young as 6 or 7 are already conditioned for a particular silhouette in their dolls, and it highlights Mattel’s challenge. Mazzocco reflects on her experience with her daughters (two Barbie fans, one not) when she talks about the diversity imperative at the brand. “I do all kinds of things for my kids that they don’t like or understand, from telling them to do their homework to eating their vegetables,” she says. “This is very similar. It’s my responsibility to make sure that they have inclusivity in their lives even if it doesn’t register for them.”

Many of the mothers in the four focus groups that Mattel allows me to observe agree with the direction Mattel is taking. And they are, after all, the ones who buy the dolls. Though young moms might be the most vocal on social media when it comes to Barbie’s body, Mattel’s extensive surveys show that moms across the country care about diversity in terms of color and body, regardless of age, race or socioeconomic position. (The majority of the women in the focus groups I watched were middle class and African American or Hispanic.)

“She’s cute thick,” offers one mom who says she has a 19-year-old son and two daughters, 3 and 5. “I have the hardest time finding clothes that are fitted and look good. It’s like if you’re bigger, you have to wear a sack. But she doesn’t look like that.” A mom sporting a tattoo says that she prefers buying My Little Pony toys to any sort of dolls to avoid the body-image issue altogether, and other mothers nod in agreement. Most say the new Barbie types would make them more likely to buy Barbie.

What I Learned Watching Moms and Kids Meet Curvy Barbie

Some say Mattel didn’t go far enough. “I wish that she were curvier,” one woman wearing her uniform from her job at a restaurant complains. “There are shapes that are curvier and still are beautiful. My daughter definitely has curves, and I would want to give her a doll like that. It’s a start, I guess.”

And despite the girls who thought the curvy doll looked fat, most of the kids in the groups I observe choose their favorite doll or the doll that looks most like them based on hair, not body shape. A curvy, blue-haired doll that many girls dub Katy Perry is by far the most popular. But when asked which doll is Barbie, the girls invariably point to a blonde.

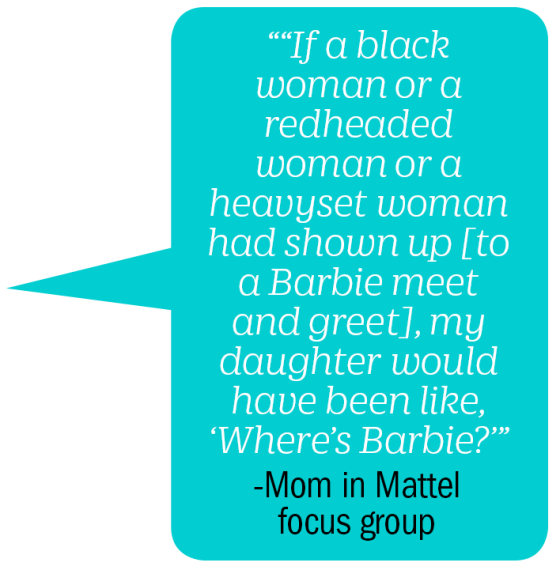

The idea that all these different dolls—none of whom look alike—can all be Barbie is confusing to moms too. “I brought my daughter to a Christmas-tree lighting with Santa and Barbie the other day,” says a mom in one of the focus groups. “If a black woman or a redheaded woman or a heavyset woman had shown up, my daughter would have been like, ‘Where’s Barbie?’” If Mattel takes away everything that makes Barbie an icon, is she still that icon? Companies work decades to create the sort of brand recognition that Barbie has. When people around the world close their eyes and think of Barbie, they see a specific body. If that body changes, Barbie could lose that status. Worse still, some customers may not like the new version. Too bad for them.

“Ultimately, haters are going to hate,” Dickson says. “We want to make sure the Barbie lovers love us more—and perhaps changing the people who are negative to neutral. That would be nice.”